When a Solo Peter Criss Asked the World to See His Humanity

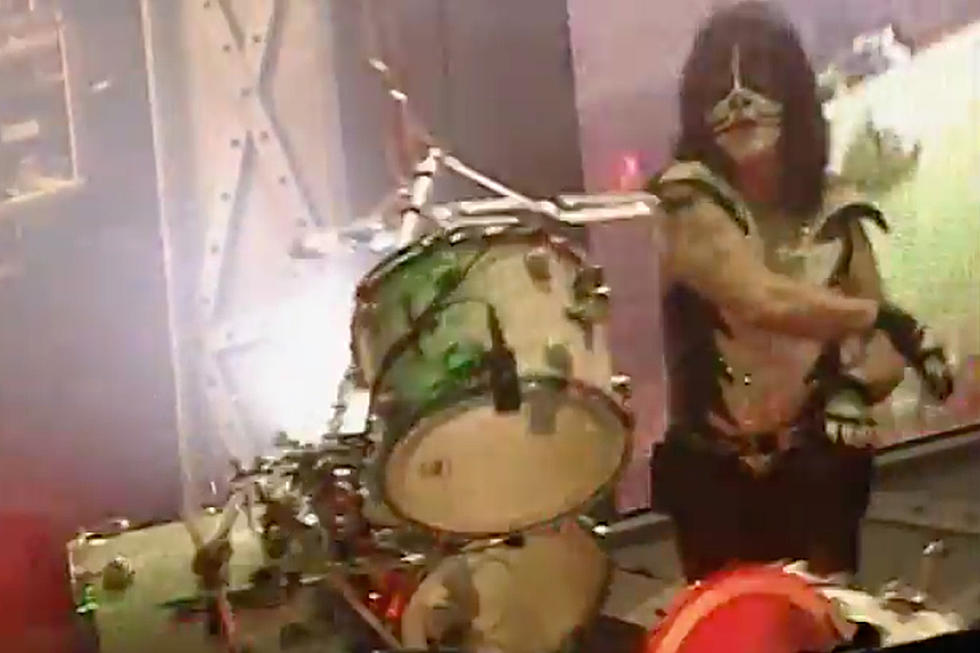

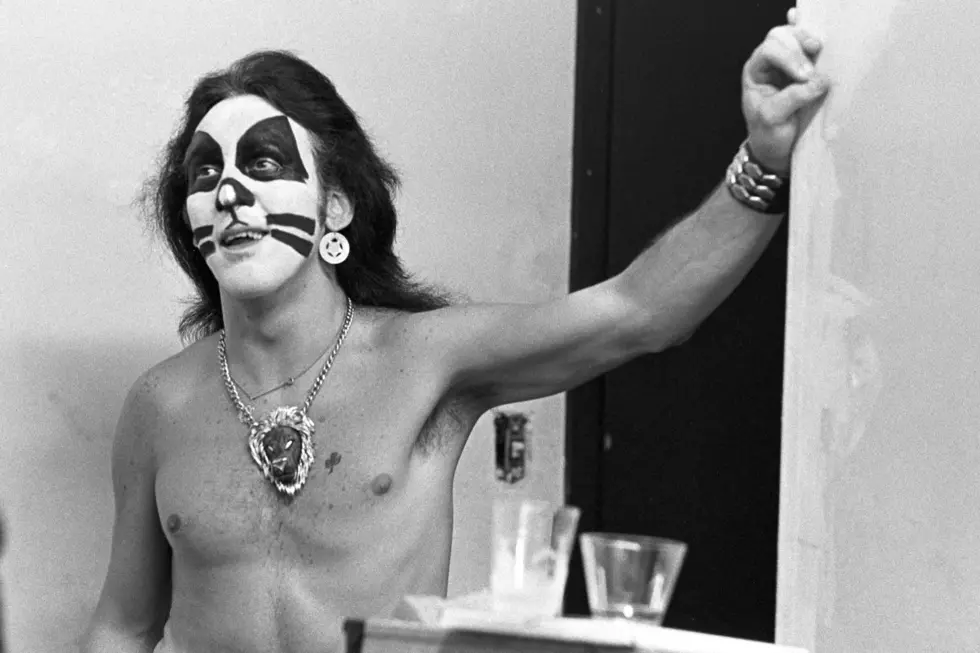

As he embarked on an ill-fated solo career in 1980, original Kiss drummer Peter Criss implored fans and music industry cohorts to see the man behind the makeup.

The drummer who created the Catman persona left Kiss for the first time on May 17, 1980, under circumstances that remain unclear. (Criss maintains he quit, while Paul Stanley and Gene Simmons have insisted they fired him.) That September, Criss issued his second solo album, Out of Control, which drastically undersold his 1978 eponymous debut, one of four simultaneous solo releases by all the members of Kiss.

After years of playing packed arenas and scoring platinum albums with his old band, Criss was back to square one, working like a dog to promote Out of Control to indifferent fans and critics. The drummer was all too familiar with the burnout artists face on the road, and on Oct. 25, 1980, he wrote an op-ed for the New York Times asking booking agents and managers to acknowledge the humanity of their clients.

"Ten years ago I placed an ad in Rolling Stone that read, 'Drummer willing to do anything to make it,'" began Criss' piece, titled "Performers Are Human, Too." "Little did I know I'd end up in Kiss doing anything and more, or what the consequences would be."

Criss went on to detail the pressures of nonstop touring and the toll it could take on a musician's personal life. "Booking agents, managers and promoters sometimes tend to forget one important point — an artist, no matter how willing he or she is to do anything to make it, is only human," he wrote. "With all good intentions, those people involved with acts can literally work them to the breaking point."

Criss confessed that he and his ex-bandmates devised some unproductive coping mechanisms to deal with the rigors of the road. "I used to pull stunts like throwing televisions into hotel pools … but not just for the fun of it," he said. "Once you've been out on the road for 200 days straight you really learn the limits of human frustration, and you go beyond the normal human limits to get rid of it."

The drummer recalled a 1978 car accident that left him hospitalized with "a broken nose, two broken hands and a concussion," which he attributed directly to his exhaustion. "So on those nights in our early years when Kiss would inflict $5,000 worth of damage to a hotel, it wasn’t just for childish joy," he concluded. "It was out of sheer frustration."

Criss said he and his fellow musicians relished a day off on the road, which gave them a chance to catch up on much-needed sleep and enjoy a nice dinner. He argued that these small doses of normalcy were necessary if artists were going to survive a grueling tour schedule that required them to be away from their families during holidays and major life milestones.

"Managers and agents should consult with and listen to the artists when planning tours, and be upfront and honest with them," Criss wrote. “Knowing the limits of an artist and the dangers of the road can mean the difference between a career of three years or 10."

He also advocated for better treatment of road crew members, whose efforts often went unnoticed even as they singlehandedly kept the show on the road every night. "Without a good road crew, you don't have a good band," he wrote. "They deserve the same kind of respect and treatment you'd expect for the band, because they work just as hard, if not harder, for a lot less pay and glory."

Criss was still willing to put in the work to help his career flourish. "If I put an ad in the paper today, it would still read: 'Willing to do anything to make it,'" he wrote. At the same time, he insisted, "Please don’t let the eagerness of performers and roadies delude you. We do have a breaking point. It's time to replace the words, 'Watch me put this TV through the window,' with, 'Why don’t we take Sunday afternoon off?'"

Kiss Lineup Changes: A Complete Guide

More From 102.9 WBLM